In today's episode, Adham Elmously and Matt Spreadbury discuss diagnosis and management of type B aortic dissections with Drs Einar Brevik and Joseph Lombardi.

What is an aortic dissection?

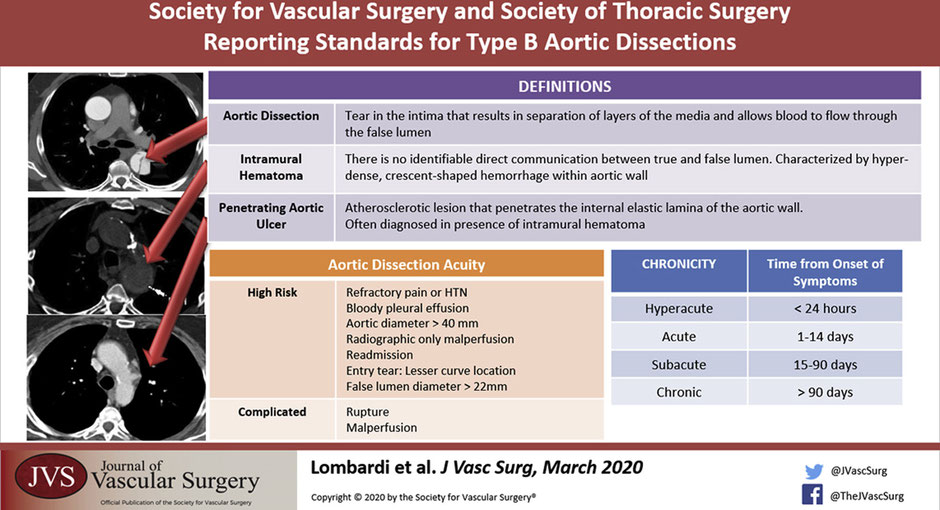

It's when a tear occurs in the intima that results in separation of layers of the intima and media and allows blood to flow through the false lumen.

How common are they and how serious are they?

Acute dissections occur around 3/100000 - 2-3x more common than ruptured aortic aneurysm. For Type A dissections, early mortality 1-2% per hour - if untreated, 20% die within 6 hours, 50% within 24 hours, 70% first week.

Main cause of death in type A is aortic rupture into the pericardium, acute aortic regurgitation, and coronary ostia compromise. While patients with descending thoracic aortic dissections are more likely to die from end organ compromise due to obstruction of visceral or extremity vessels in the acute phase of the disease.

The time frame is also important.

- Hyperacute <24 hours

- Acute < 2 weeks

- Subacute 2 weeks – 3 months -> TEVAR

- Chronic >3 months -> Chronic aneurysmal degeneration/ partial false lumen thrombosis (highest risk) = operative treatment

When we think about aortic dissections there are a few classifications, how can we break it down?

Historically, there are the Stanford and Debakey Criteria.

Anatomical Stanford

- Type A - involves the ascending aorta, 2/3 (most common)

- Type B - arises from distal to L subclavian, 1/3

Debakey

- A

-

- 1 - ascending + descending

- 2 - ascending only

- B - distal or at the LSCA.

-

- 3a - Descending aorta above diaphragm

- 3b - Descending aorta above and below diaphragm

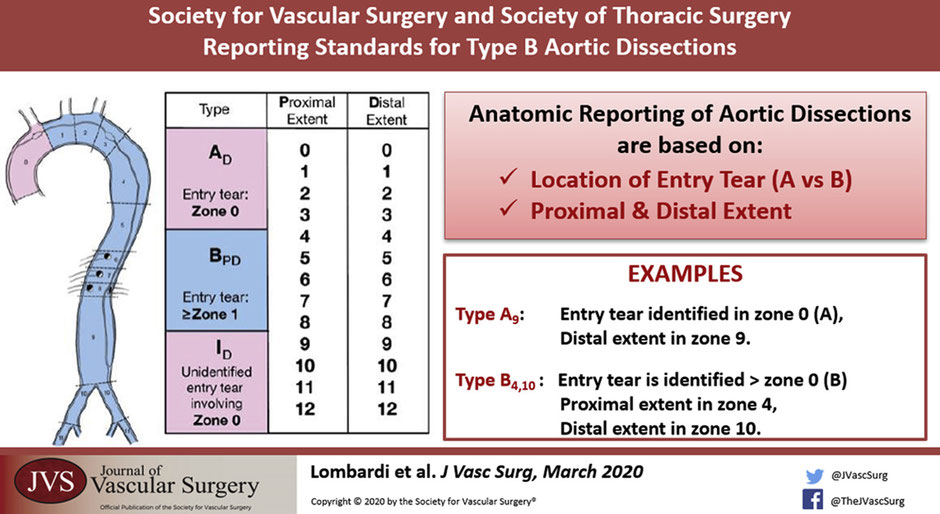

How about the new system proposed by Dr Lombardi, the SVS-STS classification system?

The new system published in 2020 keeps A and B and adds a number system which divides the aorta into zones from 0 proximaly to 12 distally in the mid SFA.

- Type A is now JUST the ascending aorta to the innominate, also called Zone 0.

- Type B is now an entry tear in Zone 1 or greater and distally to whichever zone the dissection lands in.

This anatomical classification is based on reading the CT angio. What else could we see on a CT angio that we have to know about?

So aside from the aortic dissection its self, you could see a bleb of contrast sticking out. That could be an penetrating aortic ulcer. That is an atherosclerotic lesion that penetrates the internal elastic lamina of the aortic wall.

Another key finding can be an intramural hematoma which is a hyperdense crescent shaped hemorrhage within the aortic wall. There is no identifiable direct communication between the true and false lumen. IMH are classified in the same way but with the abbreviation IMH p-d zones.

Whats the significance of these two in combination?

There is a higher chance of aortic rupture if a penetrating aortic ulcer is seen with intramural hematoma.

When a patient presents with an aortic dissection how can we classify them clinically?

- Uncomplicated

-

- Stable hemodynamics

- No evidence of malperfusion

- Pain controlled

- Complicated

-

- End organ ischemia / malperfusjon

- Rupture or impending rupture

- High risk

-

- Uncontrollable pain / hypertension

- Bloody pleural effusion

- Aortic diameter >40mm / False lumen diameter > 22mm

- Readmission

- Radiographic only malperfusion

- Entry tear on the lesser curve

What is the danger of a false lumen? How does it lead to symptoms and malperfusion? Likewise which arteries commonly branch off the true lumen?

The false lumen can lead to end organ ischemia as the intimal flap can cover the ostia of branching vessels. This can be a static or a dynamic obstruction.

Likewise it also leads to weakening in the wall of the aorta which can become a threatened rupture or rupture if the diameter of the false lumen is larger than 22mm.

The celiac trunk, SMA, right renal typicaly come of the true lumen. Left renal comes off the false.

Also the dissection most commonly goes down into the left common illiac rather than the right. You might be able to detect down stream effects of this on clinical exam with reduced left sided groin pulse.

What kind of patients get aortic dissections?

Hypertension (older patients) / cocaine or Meth (younger patients)

Marfans, loeys-Dietz, Ehlers danlos Type 4, Turners, Arteritis, Bicuspid aortic valve.

We also have a traumatic cause of aortic dissections. That being called blunt thoracic aortic injury:

- Grade 1: intima tear

- Grade 2: IMH

- Grade 3: Pseudo aneurysm

- Grade 4: Aortic rupture.

How do these patients present?

Signs and symptoms – Chest pain 90% tearing pain radiating between the shoulder blades.

Chest pain extending to the abdomen abdomen? Think mesenteric ischemia or aortic tear

Type A - Stroke 5-10%, Syncope 15%, tamponade, carotid dissection, paralysis.

Others: MI – Hypovolemic shock – leg ischemia

What is the workup?

Physical Exam – Asymmetric pulses / blood pressure differences / Diastolic murmur,

Investigations - CXR, EKG, D-dimer + Troponin, CTA, ECHO for type A.

The big distinction is to find out if this is a type A or type B because the treatment strategy is completely different.

- Type A need an emergent operation

- Type B starts with medical management, follow up CT angio +/- Trans esophageal echo in the OR. Reevaluate at 24 hours.

What are the details of Type A treatment?

Operative treatment. 30% op mortality. Cardiothoracics take the lead on this one. However vascular surgeons should be involved in the management of type A as after the repair, a type A can become a functional type B.

Type B is in the realm of vascular surgery. What is the first management step after we have diagnosed a type B dissection?

Invasive impulse therapy. That means redusing the force of transmitted impulse down the aorta. Blood pressure goals of 100-120mmHg. Hr < 60bpm.

How would you achieve that?

Start with a beta-blocker (esmolol or labetalol) first then a vasodilator (nitroprusside). This is to stop the sympathetic surge after vasodialation that could increase pressure and thus tearing forces inside the aorta worsening the dissection.

Initial CT, 72 hours, 3 months x 4, q6 months x2, q12 month. (Descending thoracic aorta that dialates first.)

Why isnt open surgery indicated for type B dissections?

Open surgery is not recommended due to the high mortality 30% if < 48 hours. 18% if > 49 hours.

In the acute setting mortality can be up to 50% with a 20% paraplegia risk. Its been described as sowing tissue paper.

What is the management plan for a complicated Type B aortic dissection?

start with invasive medical management and plan for TEVAR. The goal with TEVAR being to direct the blood flow into the true lumen and seal the entry tear. If there was a dynamic obstruction (flap occludes branching vessels.) Then TEVAR would reestablish the true lumen hence removing the dynamic obstruction. Endovascular fenestration can also equalise the pressure in the true and false lumen.

For a static occlusion there could be a thrombus or stenosis in the branched vessel so a stent might be indicated.

What are the major risks of TEVAR in the management of Type B aortic dissections?

Retrograde type A (reported 2% in literature however it can be around 20% in some experiences), 5% paraplegia, and stent induced new entry.

Is there a role for TEVAR in uncomplicated type B dissections?

The INSTEAD and INSTEAD XL trials looked at uncomplicated Type B dissections. There was NO statistical difference at 2 years comparing OMT vs TEVAR but at 5 years there was good aortic remodelling and better long term survival in patients treated in the subacute stage.

Timing for TEVAR is a difficult choice. In chronic dissections the septum thickens leading to a potentially difficult TEVAR. Anecdotally TEVAR is best at 2w-3m.

References

- Lombardi et al. Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS) and Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) reporting standards for type B aortic dissections. J Vasc Surg. 2020 Jan;71(3): P723-747

- Lombardi JV et al. STABLE II Investigators. STABLE II clinical trial on endovascular treatment of acute, complicated type B aortic dissection with a composite device design. J Vasc Surg. 2020 Apr;71(4):1077-1087.

Authors:

- Dr. Adham Elmously (@elmouslyMD) is a second year vascular surgery fellow at New York-Presbyterian Cornell/Columbia Program in New York, NY.

- Dr. Matthew Spredbury (@mattspreadbury) is a second year vascular surgery resident at Haukeland University Hospital in Bergen, Norway.

Guests:

- Dr. Joseph Lombardi (@VascSurgMD) is the Professor and Chief of Vascular Surgery at Cooper University Hospital in Camden, New Jersey and the PI on the STABLE I and STABLE II trials.

- Dr. Einar Brevik (LinkedIn) is a consultant vascular surgeon and the previous president for the Norwegian Society of Vascular Surgery.

Editor: Matt Smith

Reviewers: Adam Johnson and Matt Chia